Bitcoin Mining, Explained: History, Mechanics, Economics and Why It Still Matters

Bitcoin Mining

Bitcoin mining is one of those topics that sounds simple (“computers make coins”) until you look closely. Under the bonnet, mining is a carefully engineeredcombination of cryptography, incentive design, and game theory that keeps the Bitcoin network decentralised and resistant to attack.

At BringBackMyCrypto, we spend a lot of time thinking about keys, entropy, and what happens when people lose access to funds. Mining sits on the other side of the same reality: Bitcoin doesn’t rely on “accounts” or “password resets”. It relies on proof, maths, and rules and mining is how those rules get enforced in the real world.

Let’s walk through mining from first principles, then get properly technical: block headers, nonces, difficulty adjustments, hash rate, halvings, and the practical odds of mining a block on your own in 2025.

What is Bitcoin mining, really?

Mining is the process that:

Orders transactions into blocks,

Secures the chain via Proof of Work (PoW), and

Issues new bitcoin according to a fixed schedule.

Miners gather valid transactions from the mempool (the pool of unconfirmed transactions), build a candidate block, and then compete to find a hash of the block header that is below the network’s current difficulty target. This is a brute-force search: miners keep changing a value (primarily the nonce) and re-hashing until they find a winning result.

When a miner finds a valid block, they broadcast it. Other nodes verify it. If it’s valid, it becomes part of the longest chain (more precisely, the chain with the most cumulative work), and the miner earns a reward.

That reward has two parts:

The block subsidy (newly issued bitcoin, which halves on a schedule)

Transaction fees (paid by users who want their transactions included)

As of the April 19/20, 2024 halving, the block subsidy is 3.125 BTC per block.

A brief history of mining: from hobby to heavy industry

2009–2010: CPU mining (the “anyone can mine” era)

In Bitcoin’s earliest days, mining was done on ordinary CPUs. The network’s total hash rate was tiny by today’s standards, and the difficulty was correspondingly low. Early participants mined blocks on laptops and desktops.

2010–2013: GPU mining (parallelism wins)

People realised that the SHA-256 hashing work used by Bitcoin could be done far more efficiently on GPUs, which are built for massive parallel workloads. This kicked off an arms race: CPUs became uncompetitive.

2013–2016: ASIC mining (specialised hardware dominates)

ASICs (Application-Specific Integrated Circuits) are chips designed to do one job extremely well. For Bitcoin, that job is SHA-256 hashing. Once ASICs arrived, GPU mining for Bitcoin itself became largely obsolete. (GPUs remain crucial for many other coins that use different algorithms but for Bitcoin, ASICs took over.)

2017–today: industrial mining (scale, capital, and infrastructure)

Modern mining is often a data-centre business: rack-mounted ASICs, power contracts, cooling engineering, firmware optimisation, and increasingly sophisticated operational discipline. At the same time, hobbyist mining hasn’t disappeared but it’s become far more lottery-like unless you’re in a pool.

Why mining is important (and what breaks without it)

Bitcoin doesn’t have a central operator to decide which transactions are “real” or which blocks “count”. Mining replaces that authority with a measurable cost: work.

Mining matters because it:

Prevents double-spends by making it expensive to rewrite history.

Anchors consensus: the valid chain is the one with the most cumulative work.

Enforces monetary policy: issuance follows code, not committees.

Incentivises honest behaviour: miners are rewarded for producing valid blocks, and punished (economically) for wasting resources on invalid ones.

If you take mining away, you don’t just slow Bitcoin down you remove the mechanism that makes Bitcoin hard to censor and hard to counterfeit.

Proof of Work in plain English

Proof of Work is a system where “voting power” is proportional to expended computational work (and therefore energy, hardware, and time). A miner can’t claim they did the work they must present a block whose header hash proves it.

That’s the key idea: verification is cheap; production is expensive.

Everyone can quickly verify a block hash meets the target. But finding that hash requires brute-force searching which costs real resources.

The block reward, halvings, and Bitcoin’s issuance schedule

Block reward: what miners get paid

When a miner produces a valid block, they include a special transaction called the coinbase transaction (not the exchange “Coinbase” confusing name collision). This coinbase transaction creates the block subsidy “out of nowhere” according to the rules, plus collects transaction fees from included transactions.

Today (post-2024 halving), that subsidy is 3.125 BTC per block.

Halving: the supply schedule baked into the protocol

Approximately every 210,000 blocks (roughly every four years), the block subsidy is cut in half. The April 2024 halving reduced the reward from 6.25 BTC to 3.125 BTC, and many trackers estimate the next halving around April 2028 (expected height ~1,050,000), when the reward would drop to 1.5625 BTC.

This is what creates Bitcoin’s famous supply curve: fast issuance early on, then a long tail of decreasing issuance.

Halving calculators: useful, but know what they assume

Halving countdown tools and “halving calculators” typically estimate the date of the next halving by assuming blocks continue to arrive roughly every ten minutes (because difficulty adjusts to target that rate). Sites like CoinGecko provide halving countdown estimates and expected future halving dates.

Just remember: the exact date is not fixed it depends on actual block times.

How many bitcoin are left to mine?

Bitcoin’s maximum supply is capped at 21 million BTC.

As of 2nd October 2025, there were ~19.92 million BTC mined, leaving ~1.1 million BTC to be released.

By 17th November 2025, The Block reported issued supply surpassing 19.95 million BTC, meaning 95% of all bitcoin had been mined.

These numbers move slowly, but they do move and the closer we get to 21 million, the slower new issuance becomes.

When is the last bitcoin mined?

Because halvings keep cutting the subsidy in half, the final fractions of a bitcoin are issued extremely slowly. The common estimate is that the last bitcoin will be mined around 2140. Investopedia notes the schedule continues until the maximum supply is reached in 2140.

Hash rate: the “speedometer” of Bitcoin’s security

Hash rate is the total amount of SHA-256 hashing power miners are contributing to the network. Higher hash rate generally means more work is required to attack or rewrite the chain.

In December 2025, the Bitcoin network hash rate was around the 1.15–1.18 billion TH/s range (which is ~1,150–1,180 EH/s, or roughly ~1.15–1.18 ZH/s depending on units displayed).

A key implication: the higher the global hash rate, the more competitive mining becomes and the harder solo mining gets.

Difficulty and the difficulty adjustment factor (the “self-correcting” mechanism)

Bitcoin targets an average block time of about 10 minutes. But miners join and leave, hardware improves, and power prices change. If Bitcoin didn’t adapt, blocks could become too fast or too slow.

So Bitcoin adjusts the difficulty every 2016 blocks (roughly two weeks) to push the average block time back towards ten minutes.

If blocks were found too quickly in the last period, difficulty increases.

If blocks were found too slowly, difficulty decreases.

This is why halving countdowns are estimates rather than exact dates: the protocol keeps steering back to ~10 minutes, but real-world conditions still create variation.

Types of mining: solo, pool, and “cloud”

1) Solo mining (true solo)

You run your own mining hardware, connect it to your own full node (or at least directly to the network), build blocks yourself, and if you find a block you keep the reward.

Pros: full reward (subsidy + fees), maximum independence.

Cons: variance is brutal; you could mine for years and get nothing.

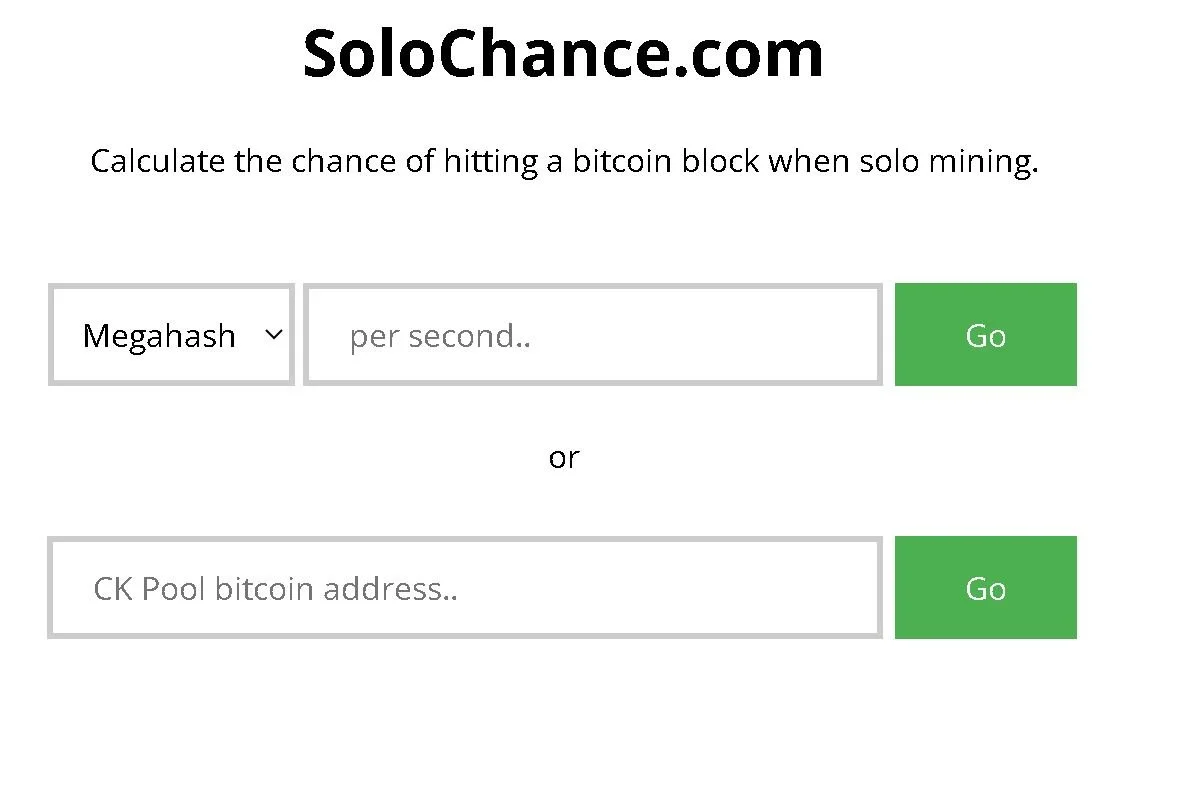

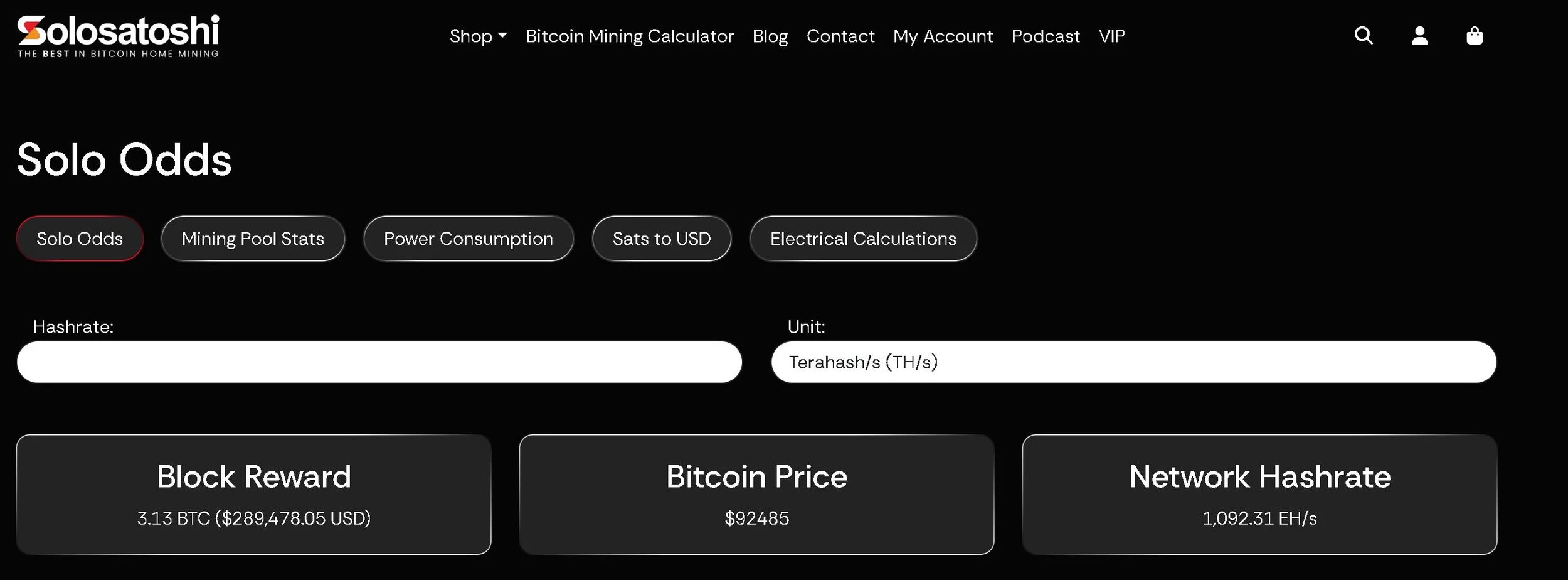

The following 2 websites provide solo mining calculators - showing clearly your chance on mining the next block.

2) Pool mining (the normal approach for most miners)

Mining pools let many miners contribute hash power and share rewards proportional to the work they submit. This smooths income you get smaller, more frequent payouts.

Pros: predictable income stream.

Cons: pool centralisation risks; pool fees; you’re trusting pool infrastructure.

3) “Solo mining via a service” (e.g., CKPool style)

Some services allow “solo” mining where you still keep the block reward if you find one, but you route work through their infrastructure. A notable recent example reported a hobbyist mining a block with a small ASIC using CKPool’s solo-mining setup a reminder that it’s possible, but extremely rare.

4) Cloud mining (be careful)

Cloud mining typically means paying a company to allocate you some hash rate in their facility (or claiming they do). Some offerings are legitimate, but the space has a long history of fraud, opaque contracts, and economics that don’t add up.

From a BringBackMyCrypto perspective: anything that puts you in a position of relying on a third party for returns especially one that controls the wallets, payouts, or contract termsincreases your risk surface. If you do consider cloud mining, treat it like high-risk counterparty exposure, not “mining like a miner”.

What are the chances of mining a block on your own?

This is where many people’s intuition breaks. The probability is not mysterious; it’s roughly proportional to your share of the network hash rate.

A simple approximation:

Your probability of finding the next block ≈ your hash rate / network hash rate

So if the network is ~1,150 EH/s and you have 115 TH/s, then:

Convert: 115 TH/s = 0.000115 EH/s

Share = 0.000115 / 1,150 ≈ 1e-7 (one ten-millionth)

Expected time to find a block is roughly:

Expected blocks to win ≈ 1 / share

Expected time ≈ (1 / share) × 10 minutes

That’s the average but variance is huge (it’s essentially a Poisson process). You might get lucky tomorrow, or never.

The Tom’s Hardware report about a very small miner winning a block underscores this: it describes a case with “astronomical odds” on the order of one in hundreds of millions per day yet still technically possible.

Practical takeaway: solo mining with small hash rate is economically similar to buying a lottery ticket that also burns electricity.

CPU vs GPU vs ASIC: what’s actually viable for Bitcoin?

CPU mining: historically important, now effectively irrelevant

You can mine SHA-256 on a CPU, but you will be so uncompetitive that your chance of success is functionally zero, while you still pay power costs.

GPU mining: not for Bitcoin (but important elsewhere)

GPUs were once dominant for Bitcoin, but ASICs outcompeted them massively. Today, GPUs matter for other coins/algorithms and for non-mining compute, but Bitcoin mining is an ASIC game.

ASIC mining: the standard for Bitcoin

ASICs provide orders-of-magnitude higher hashes per watt for SHA-256, which is what matters when difficulty and competition are high.

This brings us to a subtle point: mining is an efficiency war. If you’re paying £0.20/kWh and someone else is paying £0.03/kWh with newer hardware and better cooling, they can mine profitably at lower bitcoin prices than you can. That competitive pressure is relentless.

The technical heart of mining: block headers, nonces, and targets

A Bitcoin block contains:

A list of transactions (the block body)

A block header (a compact summary that gets hashed)

Mining focuses on the block header, which includes fields like:

Version

Previous block hash

Merkle root (hash summarising all transactions in the block)

Timestamp

nBits (compact representation of the target)

Nonce

The nonce is a field miners change to produce different hashes. The nonce is a spare field at the end of the block header used for mining essentially “number used once”.

In practice, miners vary more than just the nonce (for example, parts of the coinbase transaction can be changed, which changes the Merkle root), because the 32-bit nonce range alone isn’t enough when you’re hashing at industrial scale.

What is a “winning hash”?

Bitcoin uses double SHA-256 on the block header. A block is valid if:

hash(block_header) ≤ target

The target is derived from difficulty (stored compactly as nBits). Higher difficulty means a lower target, which means fewer hashes will qualify which means miners must try more nonce variations on average.

Mining difficulty: what it measures and why it matters

Difficulty is a relative measure of how hard it is to find a valid block compared to the easiest possible difficulty. When more hash power joins the network, blocks would come too quickly so difficulty rises, bringing block times back towards ~10 minutes.

From a security standpoint, difficulty (and the hash rate behind it) is part of what makes Bitcoin costly to attack: rewriting a block requires redoing the work and catching up with the honest chain.

The economics of mining after halvings: subsidy shrinks, fees matter more

Every halving reduces the subsidy portion of miner revenue (all else equal). Over time, mining must be supported increasingly by transaction fees the part users pay for inclusion.

What does this mean long-term?

Short-term: after a halving, less efficient miners may be forced out if price/fees don’t compensate.

Long-term: miners become progressively more fee-dependent as subsidy trends toward zero.

This is why some analysts watch “miner revenue” and “fee percentage of block reward” closely, especially during periods of high on-chain demand.

Where mining intersects with “BringBackMyCrypto” realities

Mining can feel like a separate world from wallet recovery, but they touch the same core principles:

Bitcoin is rules + keys, not accounts.

Mining enforces the rules; keys enforce ownership. Lose your keys and nobody can override it.Security is economics.

Mining security comes from the cost of doing work. Wallet security comes from the cost of guessing keys (entropy). In both cases, the system works because brute force is expensive.Be wary of “too easy” offers.

Just as “wallet recovery services” can be scams, a lot of cloud mining marketing relies on people not running the numbers. If someone offers guaranteed returns from hash rate, treat it with the same scepticism you’d apply to any custodial “investment” in crypto.Understand the adversary.

The same industrial-scale compute that secures Bitcoin also reminds us why weak passphrases and low-entropy brainwallets were a disaster: attackers can afford huge search efforts when the payoff is real. Mining is the honest version of that compute arms race.

A practical checklist: if you’re thinking about mining

If you’re considering mining (even as a hobby), sanity-check these first:

What is your electricity price per kWh?

What is the ASIC’s efficiency (J/TH)?

Can you realistically manage heat and noise?

Are you comfortable with revenue uncertainty (especially solo)?

If cloud mining: do you fully understand counterparty risk and contract terms?

If your goal is to learn mining, a small setup can be educational. If your goal is to profit, you’re competing with specialists who treat mining like an energy business.

Closing thoughts

Bitcoin mining is not just “how new coins are made”. It’s how Bitcoin stays honest without needing permission from anyone. Mining is the engine of Bitcoin’s security model, and the halvings are the metronome of its supply schedule.

If you understand mining block headers, nonces, difficulty adjustments, hash rate, and the economics of subsidy vs fees you understand why Bitcoin is fundamentally different from systems that can be rebooted, censored, or centrally rewritten.

And if you’re here because you care about custody and recovery (as many BringBackMyCrypto readers do), mining is your reminder that Bitcoin’s strongest feature is also its sharpest edge: there is no administrator to save you. Just maths, incentives, and keys.